The Focus Of Setitupbetter

This website offers a new, more logical, approach to fully understanding guitar equal-temperament intonation, leading to a more pleasing sound from your instrument. That is, understanding of bridge saddle compensation for intonation of the whole fret board (not just tuning the 12th fret note pitches), and also understanding of accurate nut compensation for open strings so they will be in tune with fretted notes, and doing so without changing the saddle adjustment).

The site will show you better intonation techniques that can give you complete understanding necessary for producing a guitar (or any other fretted instrument) with great intonation!

This is directed to all guitar players and technicians using conventional, commonly available instruments, intended for 12-note equal temperament. The Intonation of guitars (and other fretted instruments) can be greatly improved. Specialized temperaments and other unusual or costly features, such as moving or adding frets will not be covered!

Understanding will help you to determine your particular instrument needs, and will help in choosing technicians, or to using DIY. DYI is a good way to accomplish great improvements, and may be the only practical way to get big improvements, on lower-priced guitars. I recommend DYI work for those with craft skills and a healthy desire.

Frets on almost all fretted instruments are spaced accurately, and specifically, for producing the universally accepted 12-note equal temperament. This results in the ability to play pleasingly in any key without re-tuning. However, compensation of both the nut and saddle are needed to complete the intonation of the instrument.

To insure simplicity and ease of understanding, this introduction addresses the key points in understanding better intonation. Details will be presented where relevant in the in topics that follow.

Getting The Feel of How The Instrument Works

To be able to think more logically about intonation setup procedures, it helps to try to think, not as a player, but in terms of how a fretted instrument actually works. For example, as a player, we tend to think of notes on the fret board being at a distance, or number of frets, from the nut. However, the note that the guitar will sound is actually determined by the portion of the string length from the played fret to the saddle! Fret board intonation is done by moving or extending the release point of the saddle, making the vibrating portion of the string slightly longer (However, the pitch of the open string will be as if it were a perfectly flexible string without compensation.)

It is also very revealing to experiment with the pitch ranges of the strings. The nature of vibrating strings is to double the pitch frequency ( which will sound an octave higher) when you have shortened the string length by half. The spacing of the frets on the fret board are designed and made to conform to this nature.

Notice that the 12th fret is at the midpoint of the strings (ignoring compensation). A harmonic can be sounded by touching he string above the 12th fret. This produces a note an octave above the open pitch by dividing the vibrations into two equal lengths. Similarly, a harmonic over the 7th fret divides the string into 3 equal lengths, and at fret 5 dividing into 4 lengths.

Notice that the space between fret 13 and 14 is half the length of the space between frets 1 and 2. Doubling the mass of the string (by changing strings, and with equal tension) will lower the frequency to half, and sound an octave lower.

You control the tension of the strings when tuning with the tuning pegs. Changing the pitch of a fretted note on a string is determined only by the mass and tension of the string and the vibrating length of the string from the selected fret to the saddle.

The Intonation Deficiency and Its Solution.

The main problem with the regular intonation method is that (lacking nut compensation) pitches of the open strings are not in tune with those of the fret board!

The Saddle is compensated by slightly lengthening each string by adjusting the leading edge position of the saddle outward, lowering the pitch of the 12th fret.

This process is done to make notes at fret 12 an exact octave higher than the open strings. Yet it does not correct the intonation problems in other fret locations. For example you will find that the lower frets, especially on the 6th string of your acoustic guitar, and the unwound 3rd on your electric guitar, will play noticeably sharp compared to the opens.

This regular intonation process is considered to be good enough for millions of guitars, because it is very easy to do and is affordable , especially on electric guitars (with adjustable saddles for each string). There are many guitars which sound good enough for some, but in my opinion, not as good as finer instruments deserve, nor as good as persons with a finer pitch sensitivity would like.

Because of mathematical design and accuracy, the fret board, itself, should be thought of as the heart of the guitar’s ability to play in tune! (Open-strings pitches are not logical references, and need to be corrected by nut compensation.) The accurate locations of all the frets are such that, if properly compensated at both ends, the overall intonation will be excellent and pleasing to the human ear. (There are other things that affect intonation to a lessor degree, which will be covered later.)

This should illustrate why nut compensation is needed: Fretted notes are selected by pressing a string down below the fret tops with sufficient force to produce a clear tone. This causes more tension on the string, raising the pitch of any fretted note. The open strings do not have this added tension, so they will sound flat compared to fretted notes. (Most people think of this the other way around, as the lower frets being sharp, not as the opens being flat.)

There is only one way to get better fret board intonation and that is to adjust the saddle to where notes on two diverse frets are in tune with each other. For example, notes (about an octave apart (such as frets 2 and 14) are compared, and the saddle is adjusted until they are accurately in-tune with each other. This will result in all of the fretted notes being in excellent tune, especially within the range of the two selected frets, and extending for several frets beyond.

After fret board intonation is done, then, until nut compensation is done, it is necessary to tune the guitar, not by sounding the opens, but by tuning a fretted note on each string (at fret 2 or 3, for instance.

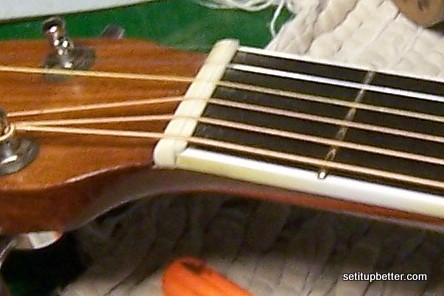

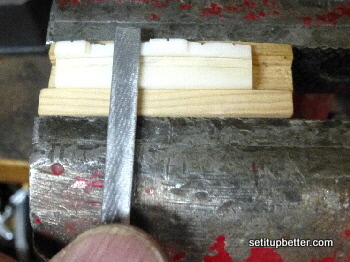

Nut compensation is done by moving the nut leading edge on each string toward the saddle, until the pitch of the open is in tune with a fretted note (at fret 2 or 3, for instance). (Tuning a fretted note may seem difficult, but you will get used to it quickly.)

For nut compensation, to raise the pitch of an open string, the leading edge of the nut needs to be extended slightly toward the saddle until the open pitch is in tune with a fretted note on that string. The amount of compensation varies for each string, mostly, but not entirely, by the core size of each string. Nut compensation consists in the completion of this process for all of the strings!

After nut compensation is done, then tuning your guitar may again be done using the open strings! Hooray!

Note: In either intonation method, it is necessary that proper attention has been applied to string choice, neck relief, fret leveling when needed, and a plan for action height at nut and saddle(s), etc, before any adjustment of the saddle or nut.

Achieve The Aha Moment!

It is very important for us to visualize what has just been described; it will be the key to true understanding of the equal temperament intonation process, to fully understand, and to know why nut compensation is separate from, and why it should not affect, nor should it be confused, with saddle intonation.

The pitch of each fretted note is the result of the length from its fret wire to the leading edge of the saddle, the mass of the string, and the tension of the string. The tension is, of course, adjusted by you, with the tuning key. After saddle compensation, tension is the only variable affecting the pitch of fretted notes (without changing the string size).

When the fretted notes are in tune, and the open string is played, the string tension is reduced, and, without nut compensation, the open string pitch will be flat. You can then compensate the nut by moving its leading edge toward the saddle until it is in tune with a nearby fretted note. So, we can see that, by shortening the nut’s length from the saddle, it raises the pitch of the open string to match that of the fretted note! Then, after nut intonation, when you tune for playing, you can go back to tuning the opens, and the fretted notes will also be in tune.

We now know that nut compensation need not affect fret board intonation, because the compensated nut is not within the vibrating length of any fretted string, and because the nut compensation was done while tuned to the same string tension and pitch as was the saddle compensation!

A Compact Overview Of What We Have Learned

Recall these basics of vibrating strings:

Tension raises pitch – Adjusted by tuning.

String mass lowers pitch – Does not usually change.

String length lowers pitch – Does not usually change.

Revue of What We Have Learned

Saddle compensation is accomplished by adjusting lengths of the vibrating strings from the frets to the saddle, while accurate fret board pitch is maintained.

Nut Compensation is accomplished by adjusting the lengths of the vibrating strings from the nut to the saddle until the open is in tune, while the pitch (and tension) of fretted notes are maintained.

Conclusions:

Saddle compensation, when done properly, results in accurate Intonation for the useful length of the fretboard.

Nut compensation, when done this way, results in Intonation of the open strings only!

Nut compensation, done properly, does not effect the fret board intonation that was done by saddle compensation!

These two processes are both necessary and sufficient for excellent equal temperament intonation.

If you fully understand these things, then you are among the very few who have thought it through! This will enable you to begin to intelligently pursue improvements to your guitar through knowledgeable technicians, or by your own work!